国際借家人連合に加盟する借主団体

Books

Reference materials

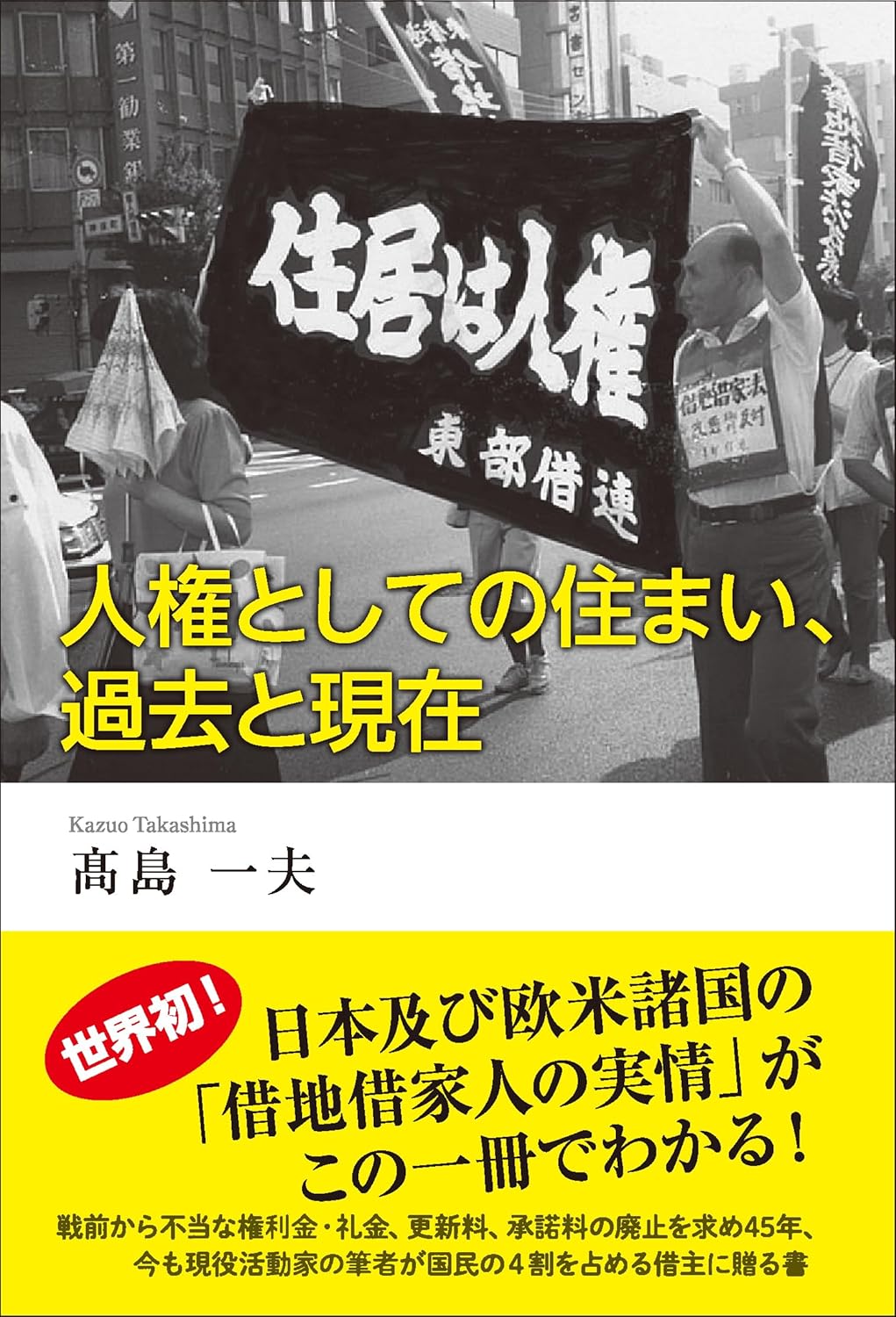

「Housing as a human right, the past and the present time」

No 1 Japan (Prewar days – the history of tenant organizations in Japan)

editing & translation by Kazuo Takashima

In September 1, 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake hit the Kanto district, centering on Tokyo and Yokohama. The number of deaths was 105,000 people, and the totally destroyed houses numbered 128,000. In those days, the population of Tokyo was about 2 million people, with 442,000 households.

About 60% of all buildings were damaged. The Japanese government quickly built temporary dwellings throughout the city and accommodated 767,000 sufferers. In October 1923, about 390,000 sufferers spontaneously started to build their own temporary dwellings by themselves using remaining unburnt timbers and galvanized sheet iron.

In 1921, the government established the “Law of Lease of Land and House,” and in 1922, “Shakuyanin Domei” (the Union of Tenants) was founded as the first tenants’ organization in Japan by Mr. Tatsuji Fuse, a lawyer, and his friends. In those days, 90% of inhabitants in Tokyo were tenants. Mr. Fuse stated that housing was at the center of human living and that tenants had the right to use a building site and build housing, even if the housing was burned. He strongly opposed landlords’ demands for evacuation from the remains of a fire. As a result, they were able to retain their housing.

However, a significant number of rent increase and eviction disputes sharply increased. The number of mediations in a summary court was 311 cases in 1922 but rose to 8,605 cases in 1924. The Union of Tenants supported tenants by distributing leaflets and pamphlets containing basic legal knowledge about rented housing and held consultations in various places.

In 1926, however, the Union of Tenants split into two organizations due to disagreements over campaign policies among leading members. Some members criticized Fuse’s actions as “petit bourgeois-like” and argued that the tenants’ movement should aim to change the political situation by getting involved in politics. Most tenants’ organizations supported the Social Public Party (Shakaitaisyuto), but in 1931, social democrats declared a rightward shift, supported the military’s aggressive war, and endorsed general mobilization.

In May 1938, the Konoe government began to regulate all aspects of public life, suppressing freedom of speech and publishing. As a result, all parties and labor unions autonomously dissolved themselves, leading to the disappearance of the Union of Tenants and other residential organizations.

(The Days After the Second World War)

In 1950, the Cominform criticized the policy of the peaceful revolution of the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) and required them to change it to an armed revolution. The JCP started armed uprisings in various places. In 1951, several policemen were killed, and over a hundred people were injured and arrested as criminals of riots.

In 1955, the JCP announced that they abandoned the policy of armed struggles, but the Japanese government still considers the JCP as a watch-list organization even now.

In 1962, the JCP established the Federation of Tenants’ Associations in Tokyo (FTAT), and in 1963, the All Japan Federation of Tenants’ Associations (AJFTA).

Kazuo Takashima was a member of the Sumida Tenants Association, which belonged to FTAT. However, he believed that tenant organizations should become independent from other organizations, politically, economically, and systematically, similar to the tenants’ organizations of the IUT. He and his friends organized a new tenants’ organization in 1979 (JTA), which was entirely independent from the JCP and withdrew from FTAT in 1965. In January 2000, JTA became a member of IUT and attended the international congresses of IUT in 2007, 2010, and 2013.

The two characteristics of the housing policies in the postwar period of Japan are as follows. One is a favorable treatment towards homeowners, and the other is an unfavorable treatment towards house or land lessees.

The former is indicated by the system of preferential tax systems and subsidy systems for housing loan borrowers. The latter is indicated by the unfair situations faced by tenants in this country.

These facts were clearly reflected in the change in the number of housing units from 1983 to 2018.

The number of housing units owned by homeowners increased by 11,152,000, while the number of private rented housing units increased by 6,808,000. However, the number of public rented housing units increased by only 54,000, and the number of UR-housing and local government corporation houses decreased by 30,000.

In September 1991, the Law of Land-House Lease was revised (*①, ②).

As a result, the housing rights of tenants became significantly weakened.

①The Term of Lease Shortening

The term of lease became shortened, and non-renewal types, such as periodic land or house leases, were enacted.

②Eased Conditions for Justifiable Refusal of Renewal

The conditions for justifiable reasons to refuse a lessee’s request for contract renewal were eased.

③Neglect of Public Rented Housing Issues

The miserable situation of public rented housing and tenants has been neglected.

The situation of public rented housing in Tokyo is as follows:

There are extremely severe conditions to qualify as an applicant for public rented housing:

1) Income Restriction: Less than 214,000 yen per month (57.8% of the average monthly income of workers in Tokyo in 2016).

2) Lottery Pass Rate: In 2017, the pass rate for being selected as a tenant was 1 in 21.5 (3,510 housing units for 75,599 applicants).

3) Old Housing Units: Out of approximately 260,000 public rented housing units, 104,000 units (40%) were built before 1975.

4) Average Floor Area: The average floor area of public rented houses was about 48 square meters, which is 52% of the average floor area of all housing units in 2018.

Particularly, the reason for the decrease in the number of house owners in their 40s and 50s was that they had a strong fear of the long and heavy burden of housing loans due to the prolonged economic recession.

Furthermore, the number of single households has been fiercely increasing, accompanied by a radical decrease in population. These characteristics have resulted from the Japanese government’s outdated concept of landownership that has persisted since the prewar period.

As a result, we have not yet been able to establish housing rights as a legal human right, although Mr. Fuse claimed that housing rights were a human and social right over 100 years ago.

In short, the outdated concept of landownership in Japan has continued to take precedence over leasing rights, maintaining overwhelming strength and serving as a strong basis for homeownership policies.